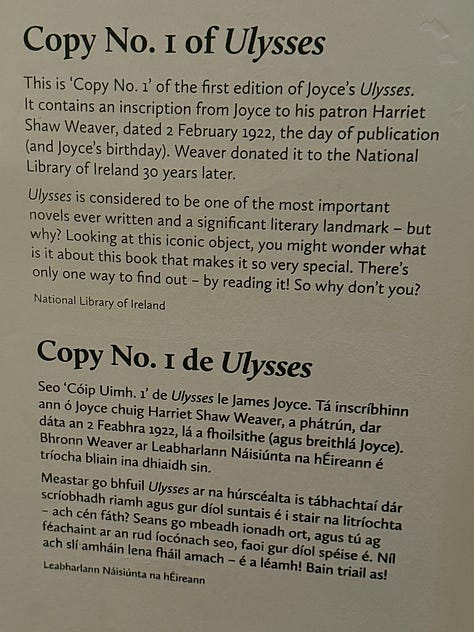

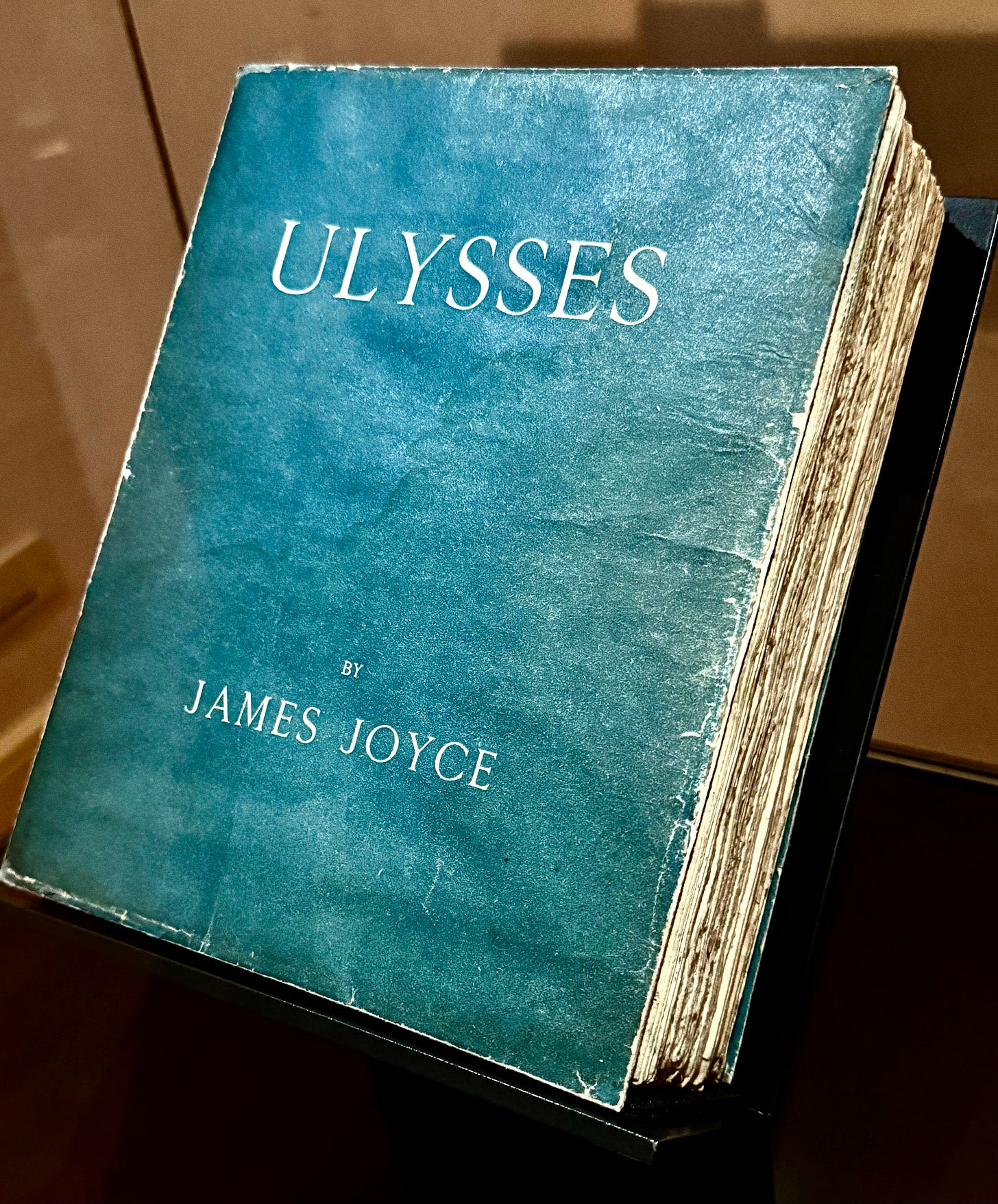

I recently visited Dublin for the first time, and there found myself standing in front of the first ever printed volume of James Joyce’s Ulysses, on display in the Museum of Literature Ireland.

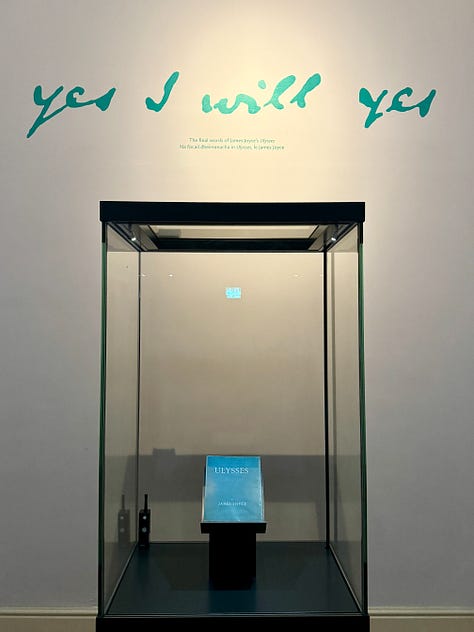

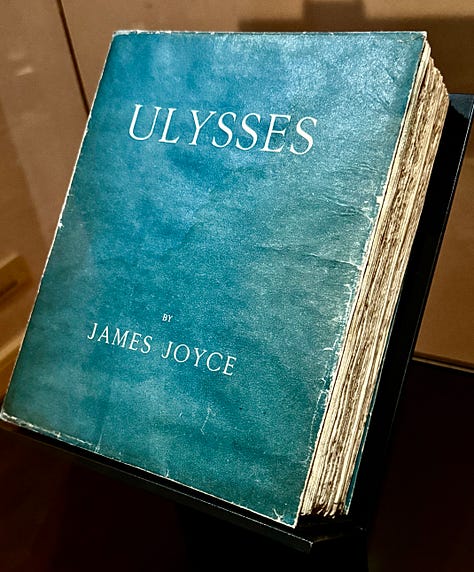

A beautiful blue cloth-bound book is encased in glass beneath Molly Bloom’s famous words, the last of the novel: ‘yes I will Yes’.

I was surprised at how moved I was to see this and other Ulysses-related fragments – some manuscript pages, other prints of the book, quotes and recordings, letters to and from Joyce.

But I should not have been surprised, for here in humble physical form was the book – form-exploding, anarchic, revered, banned, celebrated, reviled, feared and envied (including, protesting way too much, by Virginia Woolf) – that surely most embodies that mightiest quality of creative endeavour, that essential artistic spirit: disobedience.

Anne Enright here rivetingly describes this disobedience: the breathtaking refusal of Ulysses to explain itself; its linguistic acrobatics, Joyce’s ‘transgression and disruption’. And she says something which in itself is a celebration of disobedience – that ‘unreadability’ is not a problem.

More than any other book, Ulysses is about what happens in the reader’s head. The style obliges us to choose a meaning, it is designed to make us feel uncertain. This makes it a profoundly democratic work. Ulysses is a living, shifting, deeply humane text that is also very funny. It makes the world bigger.

About a third of those who attempt the book do not finish it, according to a Bloomsday poll on an Irish news website. I never considered this to be a problem. I am not sure you can ever finish Ulysses. I am certain it can never be fully understood. I think I knew this instinctively at 14; a time when I lived inside and not outside the words on the page, a time when many books were beyond my understanding, and that was just fine.

I’m writing these words now at Cove Park, an artists’ retreat in Scotland, and when I look up from my keyboard I see trees, mountains and the soft, pewter water of Loch Long. I haven’t spoken aloud in four days. Bliss.

I had intended, after the above paragraphs, to venture into a discussion about the reception of Ulysses on publication, and its influence on Western literature since. I also planned to mention some of the other rule-breaking Irish writers featured there at MOLI – Oscar Wilde, Samuel Beckett, Edna O’Brien and Anne Enright, each brightly dissident in their own particular way.

But something in my plan evaded me, something began to drag in my spirit. Something resisted.

I made more coffee. I looked out of the window. I read more about Joyce, O’Brien, Enright, Wilde, Kevin Barry and other Irish literary wild-children. I began a paragraph about why Australia’s Alexis Wright, with her lawless, time-exploding, virtually impenetrable, funny and dark and disobedient books, might be the world’s contemporary James Joyce, and how I hope the Nobel Prize comes her way some day. Then I deleted it.

I ate another piece of toast. I emailed a couple of writing friends, setting out my plans for this essay, trying to create a kind of run-up.

I took photos of the Highland cows outside my peaceful cabin.

I left my peaceful cabin to take a drive around the peninsula, bought a few supplies at the little supermarket. I returned, washed dishes, drank more coffee, ate chocolate, read on my bed and – the ultimate avoidance method, of which my consciousness is so fond – fell into a short, very deep sleep in the middle of the day.

When I woke I was forced to realise the truth. This resistance (on which I’ve written before) was telling me something.

As so often happens, it was telling me that I didn’t want to abide by the nicely logical train of thought I had set out for myself. I was bored by it before I began, and it felt somehow like a lie. Literary biography/critique is not my thing. And despite my real respect and admiration for it I don’t know anything about Ulysses, having failed to finish it twice in my adult life, marvelling and thrilling at it nevertheless. What I actually want to talk about, no matter how much I bow down to them, is not James Joyce or Alexis Wright or Irish literature at all.

So I’m not going to, thereby perhaps enacting the point of this piece, which is that an artist finally can obey no-one and nothing but their own honest instincts – or what one writer friend calls her ‘inner command’.

The strange thing to me is how difficult this always is. How, even in drafting this piece about the value of disobedience – an argument commissioned by nobody, to be read by very few, a piece written almost entirely for myself – I must first waste an entire morning wrestling with my own tedious compulsion towards to a logical and established line of thinking, only finally abandoning it when I just Can’t. Make. Myself. Do. It.

What is this about, do you think? This dogged plodding down an already well-worn path before realising it’s a personal dead end? Why are we so passively obedient to what’s gone before, until we’re not?

Partly it’s because it’s difficult to know when the inner command is just that, or when it is something else – laziness, or paucity of research, say, or lack of confidence.

Possibly the inner command is compromised by the idea that one should write something other people want to read. Writing for publication – even a tiny, virtually readerless self-published Substack like this one – is, after all, not simply writing for the self. And yet I have long been convinced that the only writing worth doing is that which feels intensely personal and private, of interest only to me.

Partly, I think, this morning’s resistance has been a sludgy reluctance to offer any kind of argument at all. Who am I to tell other artists what they should or shouldn’t do? By what expertise or authority? The idea that I have ‘advice’ to give always makes me queasy, so I should have recognised that at once as a false lead.

But – here I am, still interested in disobedience as a core tool of creative work.

The fact this concept has occurred to me for exploration right now, I realise, may have to do with the newly discovered voice of my embryonic novel in progress, and the struggle I had to find it. A struggle which has to do with a particularly female form of obedience, it seems to me.

I have found the voice now, and its discovery has the hitherto-stalled engine of my book turning over quite nicely, I hope, or will be once I’m past these months of public-facing travel and speaking, home to the blessed monotony of a regular writing routine again (2025 note to self: say no to everything).

The moment the book’s voice came alive was when I realised that a light sort of bitterness would be central to it, and to my narrator’s character. What I needed, I saw, was a voice containing hardness, and humour, and hurt. I needed a defensiveness, a spikiness bordering on spite, and I am happy at last to have found it.

It is paradoxical then, as with so much about the writing process, that landing on this tonal hostility as my book’s engine lit up one part of my brain with optimistic energy, at the same time it dulled another with a pessimistic anxiety. It took a while to dig into this, and see that the anxiety was a Woman Problem inside my writer self – a dreary, buried fear of being - not nice. This is a form of behavioural obedience from which I thought I had freed myself long ago. But no. To my boredom and shame, I discover that for a nearly-60-year-old woman like me, raised by my culture to be pleasant at almost any cost, it still takes internal nerve to commit to a book by and about a woman - a (fictional) mother, no less - which may be propelled by hostility.1

Happily, as soon as I dragged this obedience-anxiety to the surface of my consciousness I could swiftly overrule and dispatch it. I’m embarrassed now to ever have felt it, and it’s gone.

But why, ten books in, does this still happen? It seems I must continually identify and eradicate different forms of unconscious obedience in my creative self – it’s like feminism and vacuuming; once you do it you have to keep doing it over and over again, forever.

I’m betting that if you’re an artist reading this, you too might be plagued by various forms of unacknowledged and disabling obedience that might be worth examining. Let’s have a look at what some of these forms might be.

Obedience to propriety

One of the shocks of Ulysses on its release was its ‘filth’ factor (and drearily, as the Enright piece linked above notes, people now seem more interested in Joyce’s transient sexual peccadilloes than his writing). But even in our supposedly unshockable age, it can still take guts to produce work that contravenes polite social mores.2

Next time you’re feeling fainthearted, why not channel Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson who, every five years, asks his mother to spit in his face?

Obedience to artistic convention

If there’s anyone willing to explode a belief that seems beyond question, it’s Rachel Cusk. Seeing her speak at the Edinburgh International Book Festival in August was transfixing.

Any novelist who says things like, ‘imagination is not something I use, or believe in, or respect’, as she did during this session (or that she is ‘actively repelled’ by narrative), is fascinating to me. So many central beliefs about making art (that imagination is valuable, for example, or narrative is required for fiction, or even that creativity is something to be lauded) seem self-evident until someone like Cusk comes along and eviscerates them. Her Edinburgh session in conversation, with Adam Biles of Shakespeare & Company bookstore in Paris, is available (among many other brilliant events) to watch here.

If you worry that your creative approach might be too conventional, Cusk will have you going through your clichés like a dose of salts (see what I did there? ).

Obedience to big gestures

When we imagine an act of disobedience, it’s easy to imagine it should be of the explosive, attention-getting kind. But as Australian writer Amanda Lohrey told me years ago, powerful results can come from less obvious reversals and transformations:

‘You don’t have to be obviously ‘experimental’, you don’t have to write like Gertrude Stein or James Joyce — small unorthodox manoeuvres can have potent effects.’3

I love the way this more subtly disobedient approach plays out in the work of Vietnamese visual artist Thao Nguyen Phan, whose work explores the painful history of her country, but who rejects any approach that is too loud, ‘too direct or too didactic’.

‘I want to focus more on how poetry and beauty can work in traumatic situations; I want to give optimism and hope, and alternative ways of looking at these topics … I tend to focus on mundane and ordinary moments. They have their own poetry in themselves, but they are also the witness of grand narrative and grand history.’

Obedience to the market

I wrote about this in an essay years ago called ‘Reading Isn’t Shopping’, now a chapter in The Luminous Solution. The original is still online here. This is about flipping the bird to marketability, ‘likeability’, tidiness or even the desire to please a reader.

Obedience to genre

For literary fiction writers, this should be an easy one to flick off – the whole point of this otherwise useless ‘literary fiction’ category is that it is no category at all, so one book need bear absolutely no relation to the next by the same author. But it takes guts for someone known for their crime or thriller writing to move sideways, or out of it altogether. I have no idea of the pressures such an artist might face to continue in the same vein. But I do know that life is short – and surely the point of a creative life is to make the thing you want to make.

Obedience to your own success

This is something most of us will never have to worry about, hooray! But even a tiny success can make one greedy for more, and the temptation to chase it can be dangerous. To be clear, I’m in favour of success for artists – but when the way you make work is too focused outside your artist self, too focused on pleasing gallerists or publishers who want you to do the same thing you did last time, it’s worth challenging.

One way of thinking about the balance between embracing success and staying out of its grip comes from my favourite Patti Smith interview – on how it’s possible to have wide appeal but still ‘build a good name’.

Obedience to your readership or ‘fans’

This is related to the above.

I occasionally hear from a reader who informs me that ‘I have enjoyed your books in the past’, before going on to detail why they will never read me again, taking me to task for the immoral behaviour, uncivil thoughts or incorrect politics or language of my fictional characters. I can laugh this off to some extent, but each time I get a response of this kind I do have to consciously straighten my spine, accept that angering or upsetting or boring some readers is part of the job, and get on with things. I love my readers! I don’t want to lose a single one. And yet I do believe that an artist of integrity must be prepared to lose every one with each new work.

Nick Cave spoke eloquently about this in his interview with Richard Fidler on ABC’s Conversations podcast, introducing his ‘dirty bathwater’ theory of making new work. Asked about his tendency to morph and change his music, he said this:

NC: ‘You don’t want to be doing stuff you’ve already done before.’

RF: ‘Your fans probably do though, don’t they? That’s the thing.’

NC: ‘Yeah, but I feel it’s a big problem - and devastating to someone’s career - to allow the fans to dictate what you should or should not do. I say that with all the love and respect in the world. But you see it happen, and eventually I think the fans become resentful of the people they love, for not taking them anywhere. You want to take the audience somewhere, so I feel it’s necessary - and it’s my duty actually - to move forward with what I do musically, for good or for bad … It’s funny, in the writing process … I have a date where I begin the writing of the new record. And I sit down at my desk and I start to write the new record and very often it’s easy, it’s suddenly easy, and all this stuff’s coming. And I’m like, ‘Wow, this is going to be easy, this record!’ But these are deceiving ideas, I call them, or residual ideas – in that they are just the sort of bathwater of the last album, that’s just hanging around in the pipes. And for me – I think a lot of musicians are basically dealing in dirty bathwater.’

David Bowie has some similar advice:

Obedience to your own plans

As I mentioned at the start, a deep resistance to following a plan is the sure sign for me that the plan must be abandoned.

And so it is I come to an announcement about this newsletter. My plan for a whole year of ‘Subtraction’ essays has, as these things can, begun to grow oppressive to me rather than the exciting liberation it was in January. So – I’m stopping.

Subtracting Subtraction!

October will mark the end of a solid 12 months of book promotion, with all the travel and public speaking and outward-facing availability that entails. It’s been a brilliant year, while also very tiring and strangely lonely in many ways. The newsletter has been a wonderful way to keep my non-fiction writing mind active and challenged – but I’ve run out of steam for this mode of communicating, and I want to return to working as full-time as possible on my new novel. It’s time for me to rest and recharge, to open out in every way, and let my fiction brain decide, allow, what comes.

I hope it’s not a disappointment to you, my few and beloved readers. I’m going to keep this Substack alive for general announcements about my work, events and some teaching, for some semi-regular ‘what I’ve been reading/seeing/watching/cooking’ recommendations. Stay tuned for news of my exciting masterclass collaboration to come in 2025 with the brilliant Emily Perkins, for example, and hopefully a week-long residential retreat in Bali, among other things. There will obviously be no paywall for that kind of announcement! The archive – almost 30,000 words in eight full-length essays, plus last month’s lengthy Q&A on the artistic process – will stay paywalled, but new posts will be free for all subscribers.4

And who knows – I might be back some time with a new form of subtraction.

Thank you so much for your support this year. I’ve loved talking with you.

This month I’ve been …

Reading

Visiting

Coming events

There’s a different problem to resolve in this novel though, which is not just about banishing my girly people-pleasing. It’s that I know that this tonal hostility alone won’t do the job – plenty of literature lite employs female ‘sass’ in place of complexity and character, and the idea of writing in that one-note mode bores and deflates. I need things to be deeper, more complicated, if I’m to adhere to my newly stated resolve to abandon judgment while employing a voice full of judgment. Funnily enough, as soon as I articulate this impossible-seeming challenge, my writing mind fills with energy and possibility. Hooray!

It only takes guts if the ‘breach’ is sincerely made though, I think. It requires sincerity – and some originality. Cynically filling a book or a painting with violence or abjection for the purposes of shock (or worse and more common, to evoke an otherwise absent gravitas) is a banal choice, instantly tiresome and worse than primness.

https://www.charlottewood.com.au/the-writers-room.html

If any present full-year subscribers are unhappy with this arrangement and would like a discount to make up the three-month shortfall please just let me know. I quite understand that funds are tight and am happy to organise a pro-rata refund (once I work out the technology!).

If anyone needs a refund for this month's payment - I am yet to work out how to keep some bits paywalled but not take further subs - please send me a message with your email address you used to subscribe and I will figure out how to refund ASAP. Sorry about that! Best, c

Thank you, Charlotte, for the thoughts and wisdom you’ve already offered. I am full of respect for your decision, because an artist should not be compelled to write for others…as you have so vividly articulated. And you are being consistent with your own values, adhering to your needs, brave in your actions. I look forward to more wisdom, in whatever form you choose to share. Onward with the next book!