Very rarely, a work of art brings me to tears - something that happened in London recently, in the presence of Frank Auerbach’s Charcoal Heads at the Courtauld.

I suppose this is some form of the Stendahl effect – an emotion created by the presence of greatness, of witnessing something deeper or larger than words can articulate.

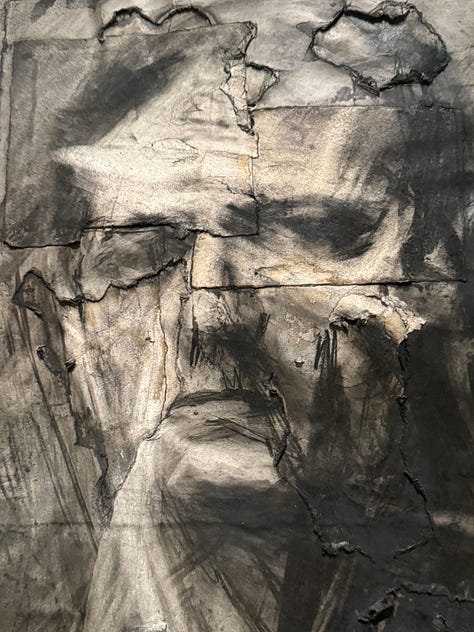

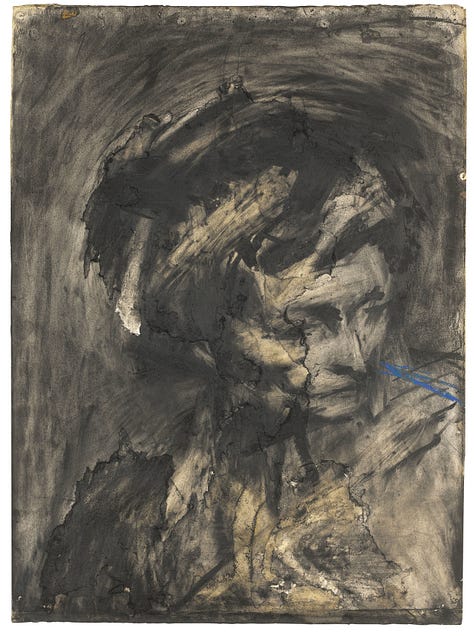

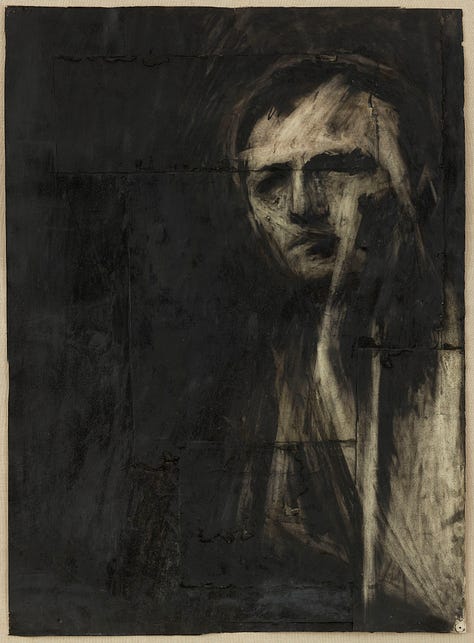

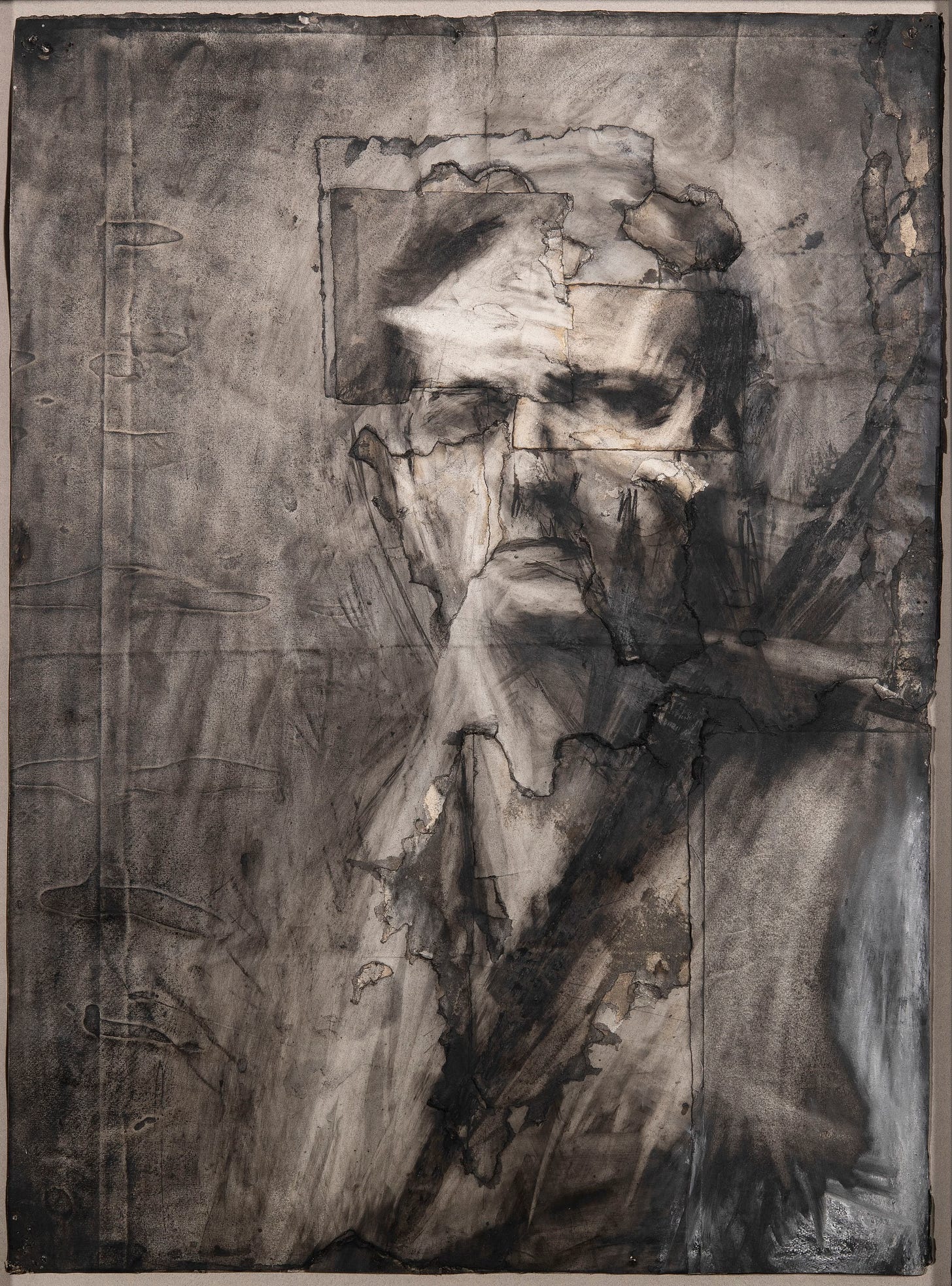

In two small rooms are collected 17 portraits Auerbach made between 1956 and 1962. Two are self-portraits, and the rest are of five different people, including his cousin Gerda Boehm. My own iPhone pictures are reproduced here by permission of the gallery alongside some of theirs, but you can see better images of the pictures at the Courtauld website and elsewhere, including of my favourite, the staggering self-portrait, via the Guardian here.

The most striking aspect of the portraits is the layered evidence of the supreme effort of their creation. As the gallery website states, Auerbach spent months on each drawing, erasing it and redrawing it over and over again in lengthy sessions with his sitters.

Sometimes, he would even break through the paper and patch it up before carrying on. Auerbach’s heads emerge from the darkness of the charcoal as vital and alive, having come through a lengthy period of struggle – the image repeatedly created and destroyed.

It's this last fact that is somehow so affecting for me. It’s not that he would make an image, throw it out and start again, a commonplace approach. The great power in these pictures comes from the fact that each rendering was made over, and on the same surface as, the ghost image of the previous version.

Ever since I saw them a month ago, I’ve not been able to stop thinking about them, looking at my photos again and again. What is it exactly, I wondered, that makes them so compelling?

As this question bobbed around in my mind, I came across two other works of art on the same day. (I came to these via Instagram, which is annoying, because every time I grow tired enough of the vacuous and pernicious nature of that platform to resolve to leave it, it throws up something glorious that I want to stick around for).

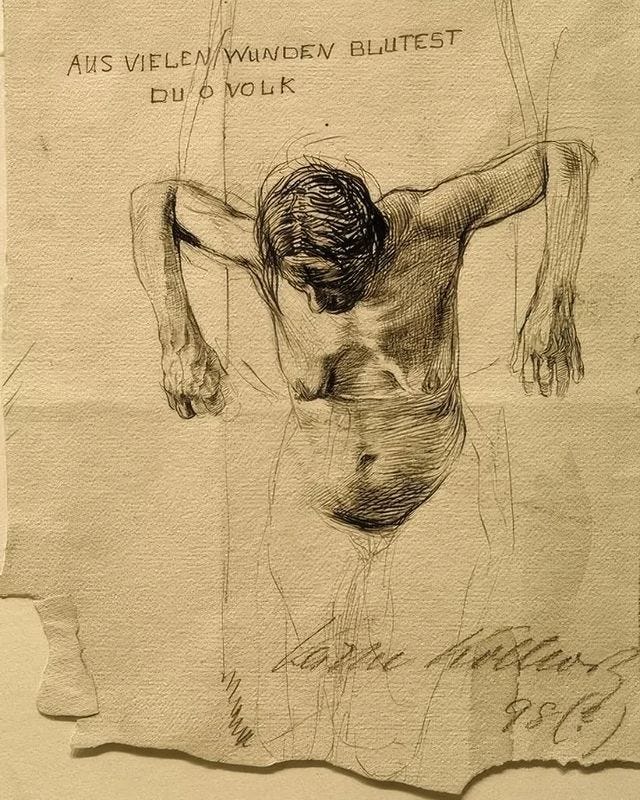

These other two were an image of Kathe Kollwitz’s study for an etching called From Many Wounds You Bleed, O People, and Lloyd Newsom’s famous DV8 Physical Theatre dance piece made into a short film, The Cost of Living. Various low-quality reproductions of the film are available on Youtube, but if you’d like to remunerate this astounding piece of creative intellectual property you can also rent a high-quality version here on Digital Theatre for just a few dollars.

I’d seen The Cost of Living film (but not the original performance) years ago and been stunned and energised by it in a way I didn’t understand. Seeing it again revived those sensations. And the Kollwitz study raised other feelings – of a great compassion and sadness. Something stirred in me. My brain was trying to make a connection, faint but pulsing, between these two works and the Auerbach portraits. It’s come to me that what they share is a rawness, an unpolished quality, and that this is the source of their tremendous power. I’m going to call this quality ‘inconsistency’. It might also be described as an instability, perhaps, or uncertainty, or roughness … the quality of messiness, of part chaos, of looseness, of mystery. Importantly, this looseness or instability is not only something occurring in the process of making the work - it’s startling because there is no attempt to hide it. It’s allowed to remain in the finished work.

From Many Wounds You Bleed, O People

Of course I’m making very sweeping assumptions about motive here, and I know nothing of the real impulses in the artist’s minds as they made these works. And I’m partly contradicting myself already; the Kollwitz, indeed, is ‘just a study’ - the final picture is a much more cohesive, polished work. But it’s the study I love, because of its uncertainty. It’s literally an unfinished image. The figure’s body trails away, she lacks limbs, and the drawing is scribbled over. The paper itself is torn, lines trail off its edge. Despite the text on the page, and regardless of any didactic certainty in the final work to come, in this drawing there is only the sense of thought in progress, of conclusions not yet reached. And in that sense, for me, lies its great poignancy.

The Cost of Living

There is nothing remotely imprecise or unfinished in the DV8 Physical Theatre dancers’ movements. Indeed, they are highly synchronous, sharp and thrillingly exacting.

Yet the work as a whole is surprising – shocking, even, in its leaps and spaces and contradictions. A dancer without legs, dance interposed with speech, characters who morph from likeable to menacing and back again, becoming never fully one ‘type’ or another. Its power comes from the elegance and truth of certain expressive movements, quite often bordering on violence, but also, crucially, from the gaps in what we expect of a narrative. People move around each other, into and out of different spaces, they pursue and are pursued, and we are never entirely certain as to why, about any of it. It has the compression of poetry. This lack of certainty lends the piece a great tension. And then there are the breathtaking shocks of simply astounding forms of human movement we have never seen before.

The Charcoal Heads

In the Auerbach charcoals the lack of polish, certainty or stability manifests almost as palimpsest ‘drafts’ made visible, one on top of another, patched and scarred and scuffed, but never hidden, never smoothed over, never attempting perfection.

As Adrian Searle wrote in the Guardian, these images

have been through innumerable scrapes – the paper so abraded by his eraser that its surface is scuffed, peeled, worn through, torn, patched, repatched (sometimes with a different sort of paper), wrinkled, worn smooth and sometimes almost burnished by his repeatedly rubbing on and taking off the charcoal, often working with his fingers or a rag but often using a hard typewriter rubber that would frequently take the surface right off a piece of paper and eventually gouge right through it.

…

Quite soon Auerbach started gluing two sheets of paper together, to double its thickness and make it more resilient. He still ends up having to make running repairs to give himself a surface and keep the drawings workable, even when the charcoal dust is building up along the contours of the patches like irrefutable forensics evidence and the eraser has nibbled at the edges which have gone all friable and beginning to look like the mice have been at them.

As a way of rendering human experience – especially when you know several of Auerbach’s subjects had been Holocaust survivors – it is intensely affecting.

A sense of disturbance

In none of these works does the ‘inconsistency’ arise from lack of skill. Crucially, it’s rather the opposite, a decision - a courageous and therefore supremely authoritative decision - to allow a sense of disturbance to pervade the work. Again, I’m not talking about subject matter, but about form and style. The disturbance in each of these works I mention comes as much from the artist’s refusal to be ‘pleasing’, or to make anything about the work palatable or digestible, as from what they are depicting. (I guess my interest in this harks back in some way to my first essay here, on subtracting ‘explanation’.)

A long time after The Cost of Living was created and performed, Lloyd Newsom spoke about his desire for ‘movement’ – disruptive, complex, even ugly movement – to replace ‘loveliness’ in dance.

I used to say for a long time that I thought that dance was the Prozac of art forms. And I think there is a problem because we train in such a regimented way and because there is an aesthetic that dominates our work … often, complex or ugly or difficult issues are glossed over because people are pointing their feet and look very lovely - you know, the concept of contemporary dance being lovely bodies doing lovely things to lovely tunes in lovely costumes …

I want to be able to use any type of movement. I remember years ago, when Pina Bausch first brought her work to London and probably about a third of the audience walked out, some muttering ‘this isn't dance’ - [but] for me it was all dance. Every movement, every gesture can be dance. Just because it wasn't on a regular beat to a regular tune doesn't mean it's not dance.

Exploding that word, regular, starts to get to the nub of things. Because there’s something so dull about regularity, uniformity. There is a tranquillising ease – even a kind of smugness – created for a viewer or reader when a work of art predictably meets one’s expectations. And ease and smugness does not make for good art.

Looking back at the Charcoal Heads, what strikes me more than anything is the palpable sense of inquiry taking place. That quest - the sense of an artist in difficult pursuit of something deeply personal, something that may never be fully explained to an audience, but whose attempt to do so anyway is powerfully visible - is always irresistible.

And always inside that quest is a genuine humility. It’s difficult to talk about humility with any seriousness these days because the word has been so degraded, and because writers, at least, are now so practised at faux-humility that any discussion of it quickly degenerates into a paradoxically boastful fetishising of failure and difficulty that I find dishonest and often self-servingly repulsive. It’s this kind of affectation Adrian Searle is referring to in his Guardian piece about Auerbach when he writes:

Some artists might make a fetish of this kind of hard labour and paper abuse, and it can easily become a tedious mannerism. Auerbach himself said that he just got on with it, and was interested to see what this curious object was that he found himself making. “It seemed expressive of the situation,” he said, and insisted he wasn’t play-acting, but had the feeling that the drawings had “risen out of the battle into being an image that stands up for itself”.

‘Just getting on with it’ is key, it seems to me. When an artist is working well, pursuing only their own questing impulse, awareness of audience falls away, knowledge falls away, competence falls away, and the work fills with energy that comes from the real risk of total failure. The willingness to show that genuine, unselfconscious struggle in the final work itself is, I think, rare, and something to be prized. That’s what I see in the charcoal heads. A woundedness coming from the practice that spreads into the form and the subject. And it’s magnificent.

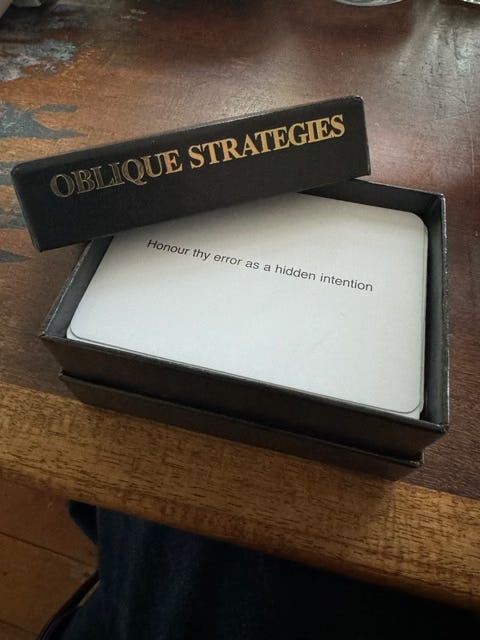

One continuous accident

Years ago the wondrous writer Emily Perkins introduced me to Brian Eno’s little box of tricks, the Oblique Strategies. A box full of cards, each carrying a statement, an instruction, a provocation. The one Emily mentioned was ‘Honour thy error as a hidden intention.’ I loved this, and I think it’s one way to begin to find this quality of innocence and inquiry. But I reckon you have to learn to recognise which mistake might become something important.

In this video, here’s what Frank Auerbach has to say on the matter:

I don't know how to do it. The things that appear on the canvas are always surprising - 999 times out of 1000 they're totally inadequate. [So] you try and go on and make them better, because one’s so ashamed of what one has done. One works out of dissatisfaction, and the actual game. There are so many considerations they're endless. The material itself plays up, the colors do funny things, you notice new configurations, new idioms - it's infinite.

I've heard other painters who, if you ask them, they actually tell you what they're going to do with the painting. I can't! I pick up the brush and look at the bloody thing and see how I can either, quite often, take it off completely, [or] how I can try to get something better. One works out of dissatisfaction. And if I sat around and waited for inspiration I don't know what I would do, but since I keep doing terrible paintings I want to go back to the easel and try to make them better because it's so shaming.’

He says his friend Francis Bacon might have said something similar – and he did:

Bacon also said this, of his Painting, 1946.1

‘One of the pictures … the one like a butcher’s shop, came to me as an accident. I was attempting to make a bird alighting on a field. And it may have been bound up in some way with the three forms that had gone before, but suddenly the lines that I’d drawn suggested something totally different, and out of this suggestion arose this picture. I had no intention to do this picture; I never thought of it in that way. It was like one continuous accident mounting on top of another.’

How to mess up in writing

Okay, but how might this all relate to making a work of fiction or non-fiction, poetry or theatre? What sort of inconsistency works in a novel, and what is just … a mess? Well, I don’t know the answer to that. And not knowing is sort of the point. The right mess-making is a matter of experimentation, risk, about-turns and flips.

One Continuous Mistake is the title of a book about writing I’ve had on my shelf for many years, by the Zen Bhuddist, writer and psychotherapist Gail Sher.

In my favourite line in this book, Sher says writers should go to the page ‘without memory, without desire, without understanding.’

Maybe this is a way in then, a portal into that possibility of a mistake becoming the work itself, a way of discovering that hidden intention which must be honoured. Turn up to the desk, as others have said, without hope or fear. Enter the material without desire or understanding, and start making. Keep going, don’t continuously erase your tracks, polishing or tidying up behind yourself as you go. Enter it entirely, eyes open, ready to ‘fail better’, loose yet alert and open to the fortuitous mistake. And there begin your quest.

This month I’ve been …

Reading

Watching

Seeing

Listening to

Superfluity, 3RRR (presented by Christos Tsiolkas, Clem Bastow, Casey Bennetto)

Novel Dialogue - Anne Enright in conversation with Paige Reynolds

Cooking

David Sylvester, Interviews with Francis Bacon, Thames & Hudson 1975 London

Wonderful piece on creativity. Thank you. The quotation about memory and desire is from psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion, who said that the therapist much approach each session "without memory or desire". Difficult to do as a therapist, difficult to do as a writer!